|

a1.4.

Teachers' perceptions of the most important skills at the end of

training

|

| After

looking at the skills and understandings learnt by teachers during

their training, discussed in Section 1.3, it was necessary to look

at how NEMP administrator training affected teachers' perceptions

of the role. Their responses to the second questionnaire confirmed

that having a good rapport with students and being a well organised

person were the most important skills for successful administration.

Teachers retained their initial perceptions about the administrator

role. This is shown in Figure 6. |

| |

| Teachers

still acknowledged that following instructions accurately was an

important skill for an administrator. However, at the end of the

training period, being a good listener to children had decreased

in importance. This may be due to teachers realising that their

role did not require them to mark and grade the assessment data

they collected and therefore they did not attach as much importance

to hearing student responses. |

|

|

|

|

|

| a1.5

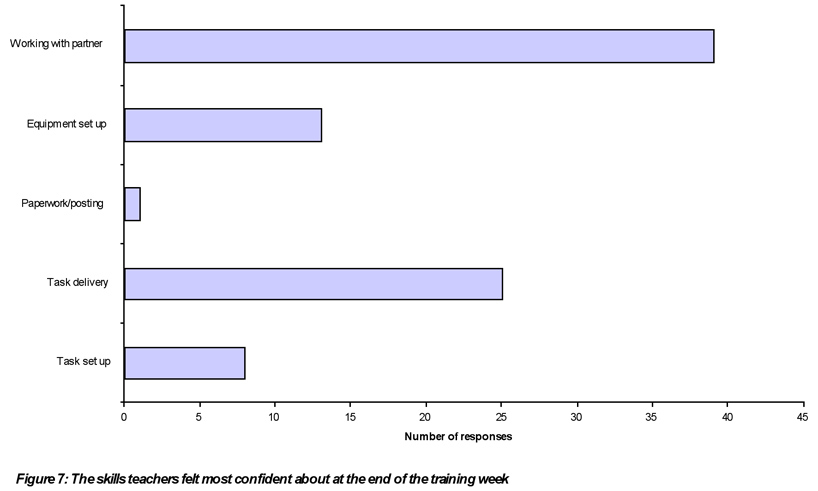

Skills teachers felt most confident about at the end of the training

week. |

| Having

identified the skills that teachers perceived as the most important

for successful administration in Section 1.4, it was interesting to

see what skills they felt most confident about. At the end of the

training week administrators rated 'working with a partner' as the

thing that they felt most confident about being able to do, as demonstrated

in Figure 7. |

|

| Several

teachers acknowledged the importance of working effectively with a

partner in order to implement the assessment tasks successfully. Their

reasons were: |

| • |

the opportunity to share and clarify ideas |

| • |

working with complementary strengths |

| • |

being able to monitor each other to eliminate errors |

| • |

collegiality |

| • |

being able to share and consequently vary the tasks administrated

|

| • |

having a duplicate set of equipment |

| • |

being able to problem solve issues with someone |

| • |

gave mutual support and confidence |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Some

journal entry comments relating to effective partnerships were made

during administration. These confirmed teachers' ideas about the importance

of successful collaboration: |

| TAJ13:

|

I

got to know my partner really well and have enjoyed the professional

discussions on a range of topics. I don't think it would be much fun

doing the admin on your own - walking into a new school on your own

would be hard, as some staff look at you with suspicion. It's good

to bounce ideas off and problem solve together. |

| TAJ7: |

The smoothness of administration depends on how well you work with

your partner. Shared work load is very important in terms of task

allocation. Task allocation did appear to be fair in most cases. |

| TAJ9: |

(My partner) and I are both well organised people who are

prepared to give and take. From my perspective, neither of us seems

to dominate. When one of us is busy the other is able to use her initiative

and help our day/week run smoothly. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Teachers

acknowledged that a positive collaborative relationship was beneficial

to the administrator role. The mutual support that a constructive

partnership provided enabled the administration of assessment tasks

to run more smoothly and provided a sense of collegiality when working

in changing environments. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| a1.6

The NEMP experience |

| Teachers

had identified the skills, ideas and understandings learnt during

the training (Section 1.3) and at the end of their training had discussed

their perceptions of the most important skills needed in the administrator

role (Section 1.4). On completion of their training as a NEMP teacher

administrator, teachers experienced a high level of satisfaction.

Teachers reported that the training programme was highly organised,

the assessment tools were well constructed and relevant. They found

the NEMP staff knowledgeable and helpful. The majority of teachers

felt confident about entering schools and working with children on

the assessment tasks. The following comments reflected these things: |

| TAJ7:

|

The

training was outstanding…the information presented was excellent,

although after day two I was thinking, “what have I got myself into?”

There was a lot to take in, but a fair bit of head space was given.

The preparation (training) was well organised. A lot of information

was covered, but it is all in the Admin. Manual; this is an excellent

working document and point of referral. |

| TAJ6: |

The training has been pretty thorough…there have been long days, two

of them in particular. I think there has been a good balance between

the areas. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| Teachers

left the training week knowing that if they experienced any concerns

or difficulties, they could contact any member of the NEMP team on

the free 'phone number, which they found reassuring. |

| TAJ5: |

I felt confident after that, that I could always contact someone at

NEMP base. It's very reassuring. |

| TAJ25: |

The 0800 number does give me confidence that help is at hand. Otago

staff are very, very helpful. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| These

comments repeat those reported by Alison Gilmore (1999) in her study

of the benefits of NEMP as professional development for teachers.

Gilmore found that “the professionalism and support from the NEMP

team was commented on frequently (35%). In contrast the number of

negative comments relating to the training week was very small. The

most commonly expressed concern (by 18% of TAs) related to the intensity

of the workload” (Section 3.1.1). Support from the NEMP office was

also identified as being important: “The consensus view was that it

was good to know that help was readily available from NEMP, which

was generally described in positive terms such as reliable, efficient

and professional (46%)”. |

| |

|

|

|

|

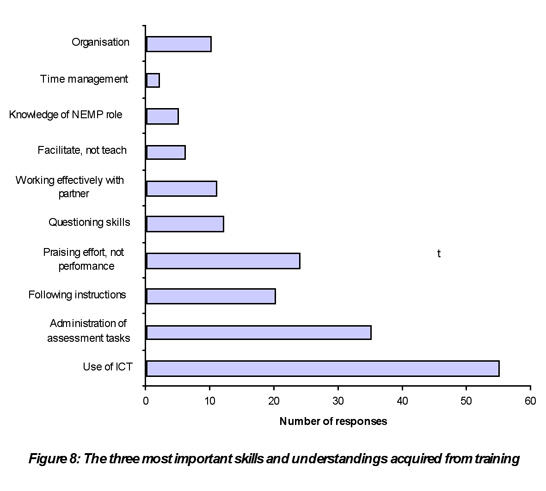

| a1.7

Important skills acquired from training identified at the end of the

administrating period. |

| At

the end of the training the majority of teachers felt confident about

working in the administrator role as discussed in Section 1.5. They

spent the next five weeks in schools, working in this role and implementing

assessment tasks. As well as completing the third questionnaire, a

number of administrators kept a journal and recorded their experiences

throughout the five weeks. In the questionnaire teachers were asked

to identify the most important skills that they had acquired from

training that enabled them to work effectively in their role.

This required teachers to reflect on both the training process and

the administration period and decide on the most important skills

they had learnt for implementing their new role. Their responses are

shown in Figure 8. The skills seen as being the most important were: |

| • |

the ability to use ICT effectively to implement tasks and record data

|

| • |

the methods for administrating tasks |

| • |

praising student's efforts and not performance |

|

It

is apparent that the training process enabled teachers to acknowledge

and incorporate some of the skills and understandings that NEMP

staff identified as being essential to implement the assessment

programme effectively. The ability to use ICT equipment had been

noted as a skill that teachers needed to learn (Figure 4). They

identified it as a skill that they had learnt during training (Figure

5). At the end of the training, although ICT skills were identified

as an important skill to have learnt, being able to work with a

variety of technologies was not perceived as a significant skill

for the administrator role. But, by the end of the administration

period, the use of ICT equipment was identified by most teacher

administrators as being the most important skill acquired from training

that was necessary to implement their role successfully. It seems

that participating in the administration process changed the perceptions

of aspects of the role for many teacher administrators.

Following instructions

was initially perceived to be an important facet of the administrator

role (Figure 2). It was identified by most teachers as being the

most important skill/understanding learnt during the training (Figure

5). After working in the administrator role, following instructions,

although still acknowledged as being a necessary skill for implementing

the assessment tasks had declined in importance (Figure 8).

Praising students'

efforts not performance was acknowledged by some teachers to be

important in their initial perceptions of the administrator role

(Figure 2). It was also a significant skill/understanding taken

up by teachers at the end of the training week (Figure 5). Administrating

the assessment tasks confirmed to a number of teachers that praising

students' efforts not performance was an important skill to use

in the administrator role (Figure 8).

Although the

administration of tasks was not rated by many teachers as being

an important skill learnt at the end of training (Figure 5) they

felt confident about delivering the assessment tasks (Figure 7).

Figure 8 shows that after administrating, many teachers felt that

the administration of assessment tasks was an important skill to

have learnt.

However, teachers

also identified other skills that they found to be important to

them in order to implement the assessment procedure that they considered

had not been part of the training process and some which had not

been part of their perceptions of the role. These are discussed

in the next section. |

| |

|

|

|

|

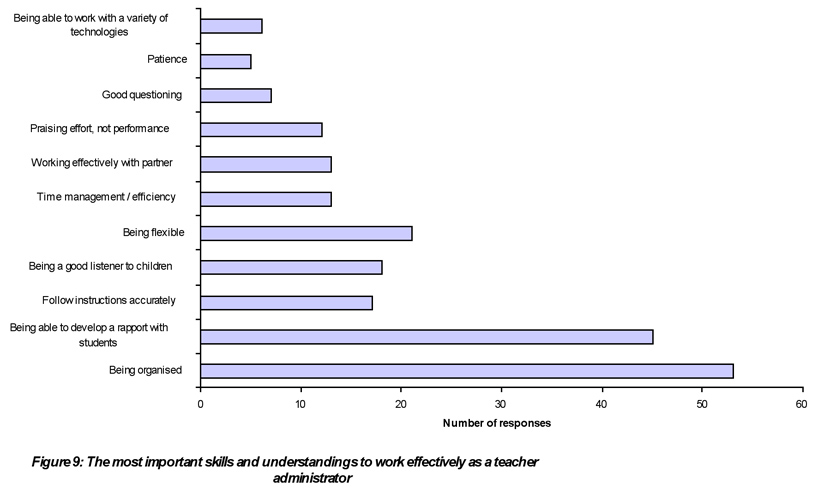

| a1.8

The most important skills required in the teacher administration role

|

| As

well as identifying the most important skills acquired from the

training programme, (Section 1.7), Questionnaire 3 also asked

teachers to identify the most important skills they perceived necessary

to perform the administrator role. Again this required teachers to

reflect on both their training process and their administration period

and think about the skills that their new role required. The most

important skills identified are shown in Figure 9 below: |

|

| The

most important skills identified were: |

| • |

being organised |

| • |

developing a good rapport with students |

| • |

being flexible |

| • |

working effectively with a partner |

| • |

being a good listener to children |

| • |

following instructions accurately |

| • |

focusing on students' effort not their performance |

| |

|

|

|

|

Being

organised and having a good rapport with students reflected teachers'

initial perceptions of the teacher administrator role as shown in

Figure 2. Teachers retained these initial ideas, which were affirmed

by experiencing their new role. Being organised (including having

good time management and working efficiently) and having a good

rapport with students are essential components of the teaching role,

which teachers acknowledged they brought with them to the administrator

role (Figure 3).

Focusing on

students' effort and not their performance was confirmed by a number

of teachers as being a necessary skill to have. Following instructions

accurately was also identified as being necessary, although its

importance had declined (as discussed in the previous section).

Being a good listener to children was part of teachers' initial

perceptions of the role. Although this declined in importance by

the end of the training period (Section 1.4) it maintained that

level of importance at the end of administration. The importance

of working effectively with a partner was included in a few teachers'

initial perceptions of the role (Figure 2). A number of teachers

thought that they had the skills of working effectively with others

(Figure 3), although it was identified as a skill some felt they

need to learn (Figure 4). Some teachers acknowledged that they were

able to develop a relationship with their partner during training

(Figure 5). Although many teachers felt confident about working

with a partner (Figure 7), the importance of a successful collaborative

partnership was not realised by many teachers until they actually

experienced working in the administrator role (Figure 9).

Although many

skills learnt in training were acknowledged as being important in

the administrator role, there were some skills that were not part

of the training process and not part of teachers' perceptions of

the role. At the end of the administration period the need for flexibility

had arisen as being an important skill to have. This had not formed

part of teachers' perceptions of the role at any stage. The need

for teachers to be flexible in the administrator role had been identified

by a member of the NEMP team (Section 1.1).

When also asked

in Questionnaire 3 to identify what was the most difficult aspect

of the administrator role, the need to be very flexible and work

effectively with a partner were identified as the most common difficulties

experienced by administrators. These are discussed in the next section.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

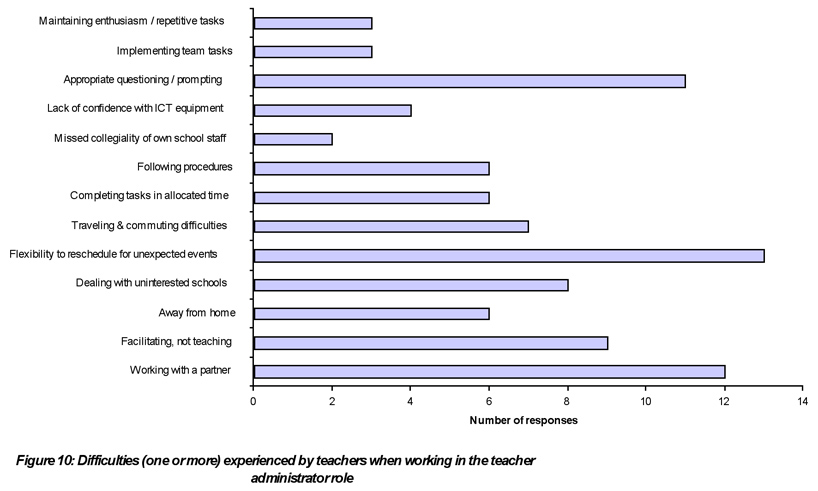

| a1.9

Difficulties experienced by teachers when working in the administration

role. |

| The

difficulties that teachers experienced when working in the administrator

role are shown in Figure 10. |

|

| It

seems that some teacher administrators were not aware that the administrator

role required a high degree of flexibility in order to accommodate

such things as individual student issues, school timetabling difficulties,

the impact of the school programme and unforeseen events. At the end

of the five weeks in the administrator role, a number of teacher administrators

included the need for flexibility as an important skill. These teachers

did not include flexibility in their perception of the role. They

felt that it should be focused on during the training process. Comments

to this effect include: |

| TAJ3: |

The role is different from what I expected…we need to make organisational

decisions and be flexible to enable tasks to be completed in this

tight timeframe. I have realised that a lot more flexibility and initiative

needs to be used. Some tasks are not cut and dry and there is the

need to work with and adapt to different children, schools and situations. |

| TAJ26: |

A rapport with students is essential, and organisational skills are

important. I do feel flexibility is more valuable than was indicated

in training - adapting to schools, prior bookings, e.g. cross country,

production, outside visitors. |

| TAJ17: |

My partner and I are working well together. We are both well organised

and flexible - probably the two most important skills required. |

| |

|

|

|

|

The

concept of flexibility is antithetical to following instructions

and following the methodical implementation of the NEMP process

that is a focus during the training week. Consequently, some teachers

had difficulty working with the two ideas. This is known as role

ambiguity, and is experienced by people when expectations within

a role are incomplete or insufficient to guide behaviour (Biddle,

1979: 323). Although some NEMP staff addressed timetabling issues

and provided anecdotal evidence of situations that may occur, it

may be that the need for flexibility has to be made more explicit.

This will serve to place the idea that flexibility is part of the

required role in the mind of the administrator so that it becomes

a shared expectation (Biddle, 1979: 117). As flexibility may not

be a skill that can be taught in a week, such as is given for the

NEMP training programme, it may well be essential to include 'flexibility'

as a prerequisite in the advertisements and information package

that NEMP uses to recruit teachers. Teachers commented to this effect

in Questionnaire 3, when identifying the skills that NEMP needed

to look for when selecting their administrators. Clarifying expectations

at an early stage in the preparation process may enable teachers

to adopt a new role more successfully as it becomes part of constructing

their perceptions of that role.

Another considerable

area of difficulty identified by administrators was working collaboratively

with a partner. Although as reported in earlier sections, many teachers

found this a valuable component of working on NEMP, when it was

not successful there was a lot of anguish and frustration. Working

with a partner was a significant change for teachers to make when

adopting the new role of administrator. Many teachers have been

through a 'socialisation of isolation' (Friend & Cook, 2003: 15)

as they have developed their professional skills and abilities.

The culture of many schools is one of independence and self reliance,

reinforced through structural isolation (Friend & Cook, 2003: 13-15).

Individualism may provide teachers with an adaptive strategy that

they actively construct to enable them to manage their relentless

work schedule. It may be due to situational or administrative constraints

which present significant barriers to doing otherwise. It may be

a preferred way of working for a number of teachers on pedagogical

or personal grounds (Hargreaves, 1994: 172-173). Whatever the origins

of working individually, it can be difficult for teachers to make

the transition from working independently to working collaboratively

in a new role, thus affecting the ability to adopt the new role

successfully.

Partner difficulties

included: having different approaches to organizing and implementing

the day; expectations of each other's approach and style which are

not fulfilled; inflexibility of partner; hierarchical relationship

of partnership. |

| TAJ25: |

I would do NEMP again despite having an 'unsatisfactory' partner.

I have missed not being able to freely discuss aspects of the programme

with her. I think being able to do that must be a learning advantage.

I know I have deliberately masked my body language and monitored my

conversation so as not to threaten my partner's position. I have tried

at times to make suggestions and be a co-team member rather than a

follower, especially when I became more confident being a teacher

administrator. But my partner had to be the boss, so I let her be.

I know I am being deliberately agreeable because the tension would

be unbearable if I wasn't, and the important thing is to keep the

programme going…it's necessary! I know I'm doing it, I don't feel

angry about it: it is just a means to an end. |

| TAJ23: |

Getting used to working really closely with someone who approaches

tasks and little things in a different way to me has been a challenge

at times. I respect the fact that she is a senior teacher and has

way more experiences than I do, but sometimes I feel that because

of the difference in age and experiences, she doesn't value my contribution

to things (as in organisation of materials etc.). |

| TAJ6: |

What I am finding a little difficult is working with a partner. Two

organised people often have their own organisation systems. |

| |

|

|

|

|

This

last comment demonstrated one of the tensions involved when skills

considered essential for the role conflict in a collaborative situation.

Although it was necessary to be extremely organised when preparing

for and implementing NEMP's assessment procedures, individual ways

of organizing things may conflict. In situations like this it is

necessary that those involved have developed the skills and strategies

to deal effectively with conflict situations to minimize the impact

of disagreement on role performance.

Administrators

who had experienced a positive relationship with their partner also

made comments concerning the potential difficulties if the collaborative

role was not successful. |

| TAJ17: |

We met up with some fellow 'NEMPers' on Friday night to share some

stories. It made me appreciate that it must be difficult to work with

a partner that you didn't get along with. Several made comments about

differences in style and organisation. |

| |

|

|

|

|

| It

can be difficult for teachers used to working in isolated classroom

situations to make the transition to working collaboratively. A number

of teachers expressed that they should have discussed issues of conflict

with their partner but did not know how to do so, choosing instead

to 'bite their tongue'. Others identified a need to have learnt some

negotiation skills: |

| TM5: |

The training should include how to work closely with another person;

we are so used to working on our own, in our own little classroom,

it is quite difficult working so closely with someone else for a long

period of time. I have talked with a few TA's and no one had a major

bust up, but there were several things that were disagreed on and

maybe learning some negotiation skills would be useful. |

| TAJ12:

|

Forming

a good, professional working relationship is essential. There are

times when it is difficult. (My partner) criticises and tries to alter

arrangements I have made - and this really annoys me. The peace is

kept because I believe that we really do have to get on as a team.

However, it isn't always easy. |

| |

|

|

|

|

At

the end of the five weeks administrating…

At times I

have felt that I needed advice on the difficulties of working

with my partner. I think some of those times have caused me the

only real stress in the job. However, we are expected to work

closely for six weeks with a stranger - in constant close proximity.

I suppose there's bound to be difficulties. Having said that,

I know she has probably found me difficult to work with too. I've

done quite a bit of tongue biting to keep the peace, but inwardly

I've been annoyed. I probably should have brought it out in the

open.

A collaborative

relationship cannot be treated as 'natural' and left to evolve entirely

on its own. It is a purposeful relationship, established with professional

goals in mind, and needs constant maintenance. Communication is

critical in order to clarify misunderstandings and confirm mutual

understandings. Collaboration requires parity among participants,

where each person's contribution is equally valued. It is essential

for individuals to make the necessary adjustments in order that

they have parity as they work together on a specific collaborative

task, even if they do not have parity in other situations (Friend

& Cook, 2003: 6). A perceived disparity in professional ability

seems to have been a cause of partnership difficulties in several

administrator situations. Instances of this occurred when a classroom

teacher was partnered with a teacher from a management background

and the classroom teacher felt that her comments, systems of organisation

and ideas were not valued. It also occurred between teachers with

significant differences in their amounts of teaching experience,

where the more experienced teacher dominated the partnership leaving

the other teacher feeling under-valued.

Salend and Johansen

(1977) focused on the concerns teachers have about working collaboratively

and how they addressed and resolved those concerns. They identified

factors that contributed to the development of successful collaborative

work. They suggested that training in adult-adult communication,

active listening, conflict resolution and problem solving needs

to be provided for adults becoming involved in collaborative work

(1977: 8). Individuals need to learn ways to negotiate working effectively

together that enables honest communication, risk taking, acknowledging

the perspectives and experiences of their partner and letting go

of absolute control (1977: 9). Friend and Cook, (2003:170) acknowledge

that professional educators have been well trained to work with

children but propose that they know surprisingly little when it

comes to the adult-adult interactions that drive collaboration.

They suggest that considerable attention should be given to assisting

educators to develop positive communication skills with other adults.

This enables them to attend to relationship issues right from the

beginning, and as they rise along the way, in order to develop the

trust required to give and receive authentic criticism of one another.

By the end of

the administrating period, more administrators acknowledged that

working effectively with a partner was an important skill to have

developed (Figure 9). It appeared that having performed the role

of teacher administrator and developed a better understanding of

the administration process and the procedures for setting up that

process, the importance of a good collaborative working relationship

with one's partner was reinforced.

Another difficulty

experienced by administrators was questioning and prompting students

appropriately, which required administrators to deviate from the

script. For a number of teacher administrators, 'following the script'

in order to facilitate the assessment procedure was a difficult

task (Figure 10). Administrators recognised the importance of following

the script accurately in order to acquire valid data, and included

it in their most important ideas learnt during the training week

(Figure 5). Most of the difficulties with following the script arose

from the use of prompts and questioning in order to elicit more

information from students (Figure 10). Administrators felt that

they needed more guidance as to what was acceptable prompting if

the 'script' was not comprehended by students, as they were unsure

as to how much they could acceptably deviate from the script in

order to elicit a response. Following the NEMP process accurately

is a crucial part of taking on the administrator role. By acknowledging

it as one of the most important aspects of the role, teachers demonstrate

that they have an understanding of what is required of them in their

new role. However, it seems that in order to adopt the role successfully

there is a need to be prepared differently for this aspect of the

role before they go out and work in schools.

Comments received

throughout the administration procedure include: |

| TAJ17: |

Sticking to the script has been the most difficult, especially when

things are worded in a way that students don't understand. I am not

sure how much prompting is acceptable…I don't think this was covered

in our training - maybe good and/or not recommended exemplars would

be helpful. |

| TAJ13: |

Not sure how much intervention I should be giving to keep students

on the right track - how much to leave them even if they are going

wrong. Got my report - got pulled up on this, so obviously I need

to be more 'hands off' with my prompting. It's good to get that feedback.

Probably more emphasis could have been made on this aspect of training. |

| 2

weeks later |

|

|

|

| |

The

prompting is still something I struggle with. Some suggestions on

a laminated card that you could have in front of you would be useful

- not enough emphasis on this during training. |

| TAJ12:

|

Not

prepared well for how far the prompting can go. In my efforts to get

children to explain ideas I'm worried if I'm over-prompting now |

| |

|

|

|

|

| NEMP

staff also acknowledged that keeping to the administrator script in

the manuals posed difficulties for administrators: |

| NEMP2:

|

Definitely

forcing….you know how they read from the script, they have to stick

to the script but in the end it's sounding very like, rote and there's

no…I think the student's feeling quite isolated in a way sitting there…so

that's not a good thing, I see that quite a bit. Also, their prompting

can be too leading…prompting is very important, that they don't tell,

give answers as they prompt, or they prompt too hard, forcing the

child instead of giving them time; it's very important to give them

time…pretty quickly you've got to have a rapport with that child and

work out exactly when you think they're going to speak…it's quite

hard really. |

| After

watching the first week of Year 4 administrator video tapes |

|

|

|

| |

Prompting

and reiterating the questions was not so good. |

| NEMP4: |

It is difficult to get across to TA's how to rephrase things without

being leading…this leads to the tension between them following the

script and paraphrasing without giving a direction |

| From

comments received it is apparent that following instructions and sticking

to the script in order to follow the NEMP process was a problem for

the administrators. A number of administrators did not successfully

integrate the skills of prompting and questioning appropriately. When

working as an administrator, this caused conflict between how they

perceived their role and what the role seemed to require. As discussed

in Section 1.8 concerning the notion of flexibility, this again appeared

to be an instance of role ambiguity (Biddle, 1979: 323) where there

is insufficient knowledge to guide behaviour. This created difficulties

for the successful adoption of the role. |

| |

|

|

|

|